I Still Don’t Know What to Do About Science

As he approached the classroom door, he paused and thanked me for letting him sit in on my physics class for a few minutes. Then, as he turned to leave, he said something that I’ve never forgotten: “I’ve been doing this for twenty years, and I still don’t know what to do about science.”

He was part of an accreditation team visiting our school and I believed he was affirming something I already knew; classical Christian schools were still wrestling with how science fit into their mission. His words communicated the same mixture of frustration and resignation I’d heard from so many teachers and administrators over the years so I wasn’t surprised by them.

Most of us who teach in this movement are keenly aware that there is a clear vision for the humanities, but when it comes to science, things get rather blurry very quickly. Some schools rely on public-school textbooks and add Bible verses while others treat science as an afterthought—a modern subject that doesn’t quite belong in the classical world.

After teaching nearly twenty-five years in classical Christian schools, I can confidently say that very few of us—science teachers included—really understand the unique challenges and opportunities that come with teaching science in this setting. And, while conversations about teaching any academic discipline in any setting typically begin with curricular and pedagogical considerations, I believe that, before we consider those things for science in the classical Christian school, we must agree on something much more fundamental and that is that robust science instruction is essential to classical Christian education.

Here’s why.

Science is a Gift of the Classical Tradition

Science didn’t appear out of thin air—it grew out of the same soil that produced the rest of the Western intellectual tradition. The Greeks, living more than two thousand years before the birth of modern science, began to look at the world with a new kind of wonder.

Before that shift, Greek mythology explained nearly everything. The gods were behind every storm, earthquake, or harvest. Nature was ruled by divine caprice and, as a result, was a place of chaos.

However, in the sixth century B.C., something remarkable happened. A few thinkers—men like Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus—began asking what instead of who. “What is the world made of?” “What causes lightning?” “Why does the earth shake?” They started looking for order instead of whim, for natural explanations instead of divine tantrums.

Their approach was novel: it was rational, evidence-based, and open to debate. This new generation of thinkers didn’t just tell stories—they proposed ideas that could be tested, challenged, and refined. They saw the world as an orderly place governed by patterns and principles. The Greek word for that kind of ordered world was kosmos—from which we derive our word cosmology.

This was the birth of natural philosophy, the forerunner of modern science. And that means science, far from being an outsider, is one of the great achievements of classical civilization—an essential piece of the Western inheritance we claim to cherish.

So, if we believe classical education is about passing on the wisdom and achievements of the West, then science belongs right alongside Homer and Plato, not as an intruder, but as family.

God Reveals Himself Through His Creation

Of course, classical Christian education isn’t just about preserving a cultural tradition—it’s about seeing all truth as God’s truth. And Scripture is unmistakably clear that creation itself reveals God.

In Romans 1:19–20, Paul writes

“For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.”

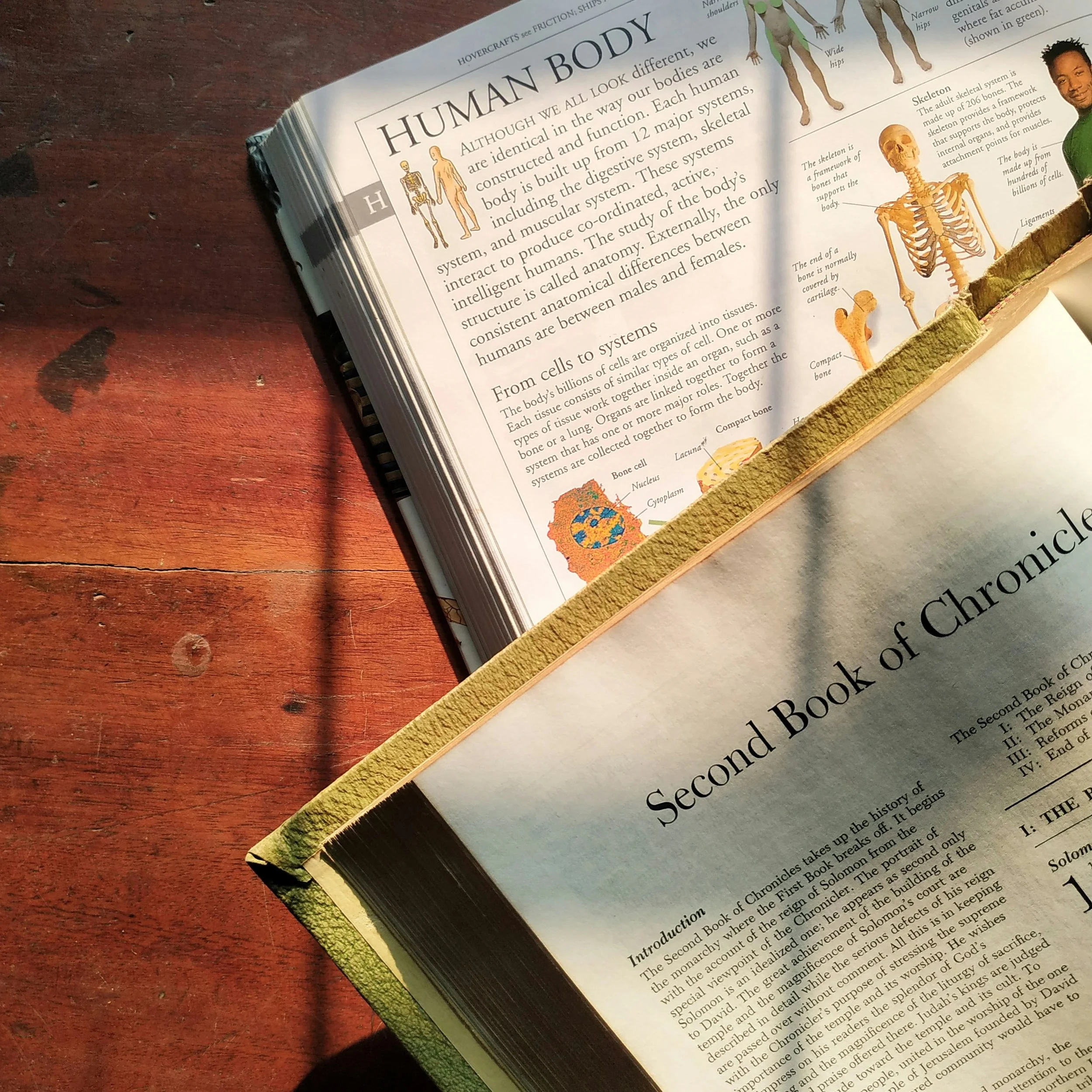

Creation is not silent—it declares. “The heavens declare the glory of God,” says Psalm 19:1. Psalm 139 reminds us that God knit us together in our mother’s womb and Psalm 95 proclaims that the sea and the mountains belong to Him because He made them.

From the farthest galaxy to the smallest cell, God’s fingerprints are everywhere. He doesn’t reveal Himself completely in nature, but He does reveal Himself truly—His power, wisdom, and majesty.

And that means when we study His creation—whether in physics, chemistry, or biology—we’re not just collecting data. We’re learning to recognize His handiwork. The science classroom, rightly ordered, becomes a place of worship, where curiosity and reverence meet.

If creation reveals the Creator, then studying creation is an act of obedience and delight. That’s why science isn’t optional in a Christian school—it’s essential.

Faith and Science Work Together

Many people today assume faith and science are enemies locked in a centuries-long war, but that idea is mostly a modern invention, born in the late 1800s from writers who had political and professional reasons to pit the two against each other. For most of Christian history, believers saw faith and reason as allies.

Augustine of Hippo, writing in the fifth century, offered one of the most thoughtful visions of how theology and science can walk hand in hand. He made four points that still guide us today:

All truth comes from God. There isn’t one kind of truth for theology and another for science. Whatever is true in nature is God’s truth, because He made it.

God reveals Himself in two “books”: Scripture and nature. Both come from the same Author, and therefore, they cannot contradict one another.

Both must be studied carefully. Scripture requires faithful interpretation; nature requires careful observation. Both disciplines demand humility and patience.

Knowing nature deepens our faith. When we study creation, we see more clearly the order, wisdom, and power of its Creator.

For Augustine, theology and what we now call science were not competing domains but complementary ways of knowing. Each sheds light on the other.

And that’s the vision we should recover in classical Christian education—students who see no tension between loving Scripture and loving the created world, between faith and reason, between prayer and experimentation.

Why Science Matters in Classical Christian Schools

Science belongs in our classrooms not just because it’s part of the Western tradition or because it reveals God’s glory, but because it helps form the kind of students we hope to produce—curious, humble, discerning, and full of wonder.

When students study creation carefully, they learn habits of mind that echo the Christian virtues: patience, attentiveness, honesty, and reverence. They learn to see order where others see chaos, and to trust that truth, wherever it is found, belongs to God.

Classical education seeks to form whole persons—hearts that love rightly and minds that think clearly—and because robust science instruction can contribute to that formation, it is essential to classical Christian education.